How the Turkish origins of ‘chock-a-block’ were lost

As per the previous two posts, [here] and [here], ‘chock-a-block’ is an English borrowing of the Turkish idiom çok kalabalık, and the orthodox etymology, which maintains it is a term from naval mechanics, makes no sense. But since this is so obvious, it now becomes mysterious why no one already knows it. How did the Turkish roots of ‘chock-a-block’ come to be lost?

Perhaps nothing more need be said than that word origins are being forgotten all the time, and that false etymologies can easily acquire currency given the human tendency to make something up rather than admit a gap in knowledge—especially a gap concerning something so domestic as our own native language.

Yet this is not satisfying. For the origin of ‘chock-a-block’ does not lie in a singular act of linguistic invention that was never written down, nor is it a borrowing from a dead language now lost to history, but can easily be seen in the concordance in sound and meaning between expressions in two languages that are perfectly well and alive. Hundreds of millions of native English speakers have visited Turkey in the centuries since the term took up residence in English, and is it credible that really none of them ever heard the phrase çok kalabalık? Yet the spell of the fabulous nautical etymology has apparently been so strong that the concordance was never recognised.

The universal insistence on the fabulous etymology, in the face of the obvious, suggests to me that the roots have not been just carelessly forgotten; rather, some unconscious social force has been at work, in its own little way, to ensure that the Turkish origins remain buried. Perhaps a journey back through the history of the term will give us a glimpse of it.

Down Another Rabbit Hole

The oldest usage of ‘chock-a-block’ recorded in the OED is from a 1799 dictionary of nautical terms: ‘Mot qui signifie qu’on ne peut plus haler sur un palan par la jonction des poulies… You are chock-a-block. Les poulies sont à joindre’ [Vocabulary Sea Phrases vol. I. 43]; the second edition of that dictionary moves the definition to the entry for ‘block-a-block’ and says the terms are ‘the same’.

The terms certainly are the same; but the OED records ‘block-and-block’ very much earlier, from 1627:

When wee have any Tackle or Haleyard to which two blocks doe belong, when they meet, we call that blocke and blocke. [J. Smith, Sea Grammar]

This shows that the transfer of çok kalabalık into English must have happened earlier still, since the origins of the term have already been forgotten, and the author, J. Smith, has seemingly corrected the sailors’ usage by replacing that nonsensical first ‘chock’ (see the previous post) with what logic told him ought to be there: namely another ‘block’. But who is this J. Smith?

Not Quite a Disney Hero

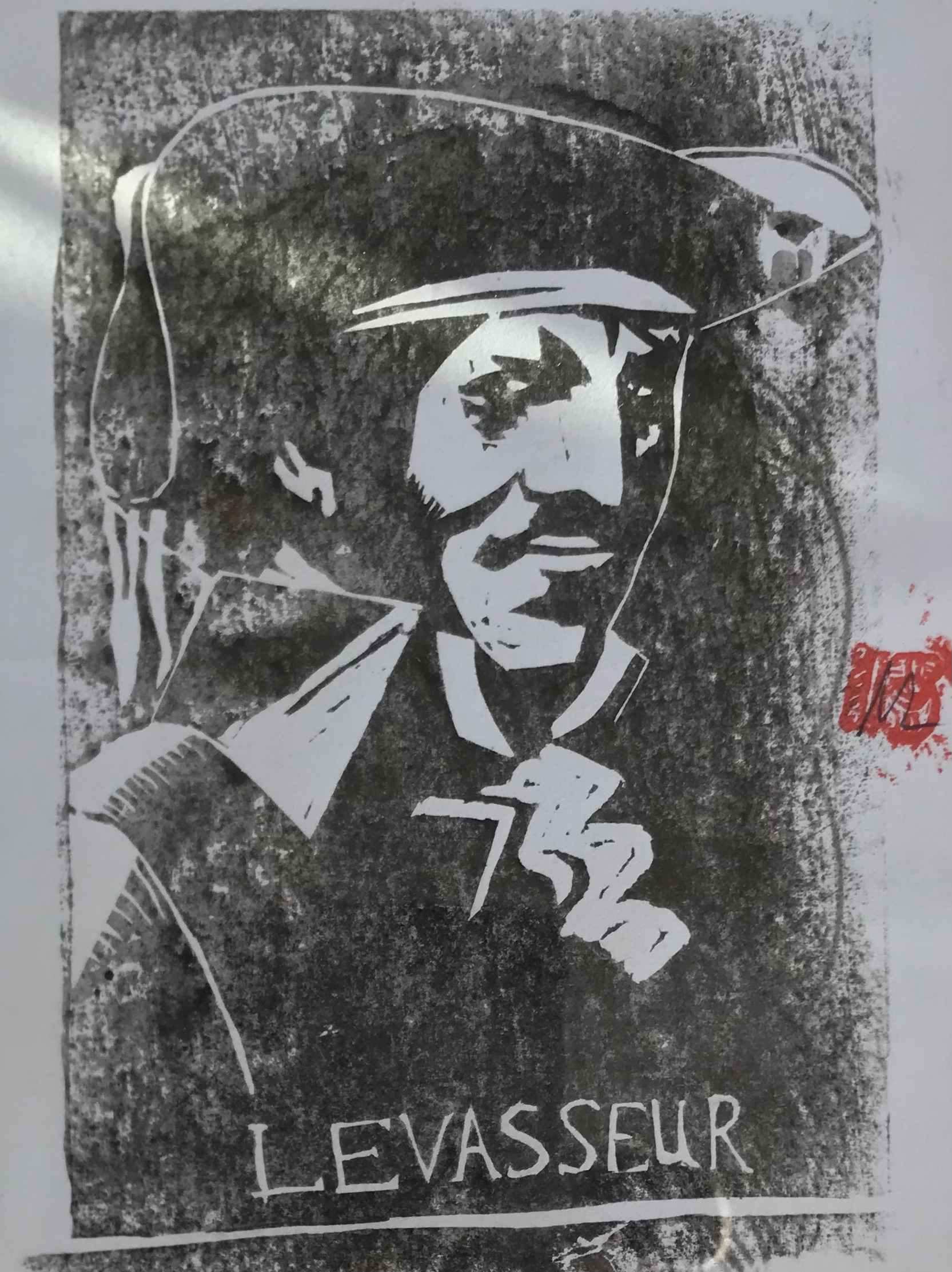

He would be known today chiefly through his appearance, voiced by Mel Gibson, as the lover of Pocahontas in the 1995 cartoon; but the real John Smith (c. 1579–1631) was a mercenary, pirate, and explorer. It has been remarked that his life was not particularly unusual for a man of the Elizabethan era: the son of a yeoman farmer—and therefore not of noble birth—as a child he was apprenticed to a merchant in King’s Lynn, but abandoned this position aged sixteen to join in the European wars, desiring especially to fight the Turks. Coming eventually to Wallachia, during a pause in the general warfare he killed three Ottoman soldiers in successive duels, for which he was knighted by Báthory Zsigmond, Prince of Transylvania; but shortly afterwards was captured and in 1602 sold as a slave in Istanbul. Given as a gift to a Greek noblewoman whose name Smith records as Charatza Tragabigzanda, they had (he implies) the beginnings of a romance, until he escaped by killing her brother, disguising himself in his clothes, and making his way along the public highway to a Russian fortress, his slave’s collar still fixed around his neck.

With his wealth restored to him by Zsigmond, he returned to England and invested in the newly chartered Virginia Company, sailing west in 1606 to establish the Jamestown colony; but the hereditary noblemen among the colonists despised him for his low birth and conspired during the voyage to have him executed. With the gallows already built, he escaped death when Company orders were unsealed designating him as one of the colony’s leaders; but the colony itself was wracked by starvation and disease, largely because the nobles refused to work, expecting to be served by the commoners. Thanks (so he later claimed) to the intercession of Pocahontas, Smith entered into reasonably friendly relations with the Powhatan tribe, within whose territory Jamestown had been established, and from them they received essential supplies. Eventually becoming the leader of the colony, Smith denied the hereditary nobles their assumed right to the common store, asserting instead the communist principle ‘he that will not work shall not eat’. The fortunes of the town improved; but not long after he was injured in a suspicious dynamite explosion and forced to return to England.

Once recovered, in 1614‒16 he made his final voyages to map the coasts of Maine and Massachusetts—to which area he gave the name New England—and then retired to write. The book cited by the OED, his 1627 Sea Grammar, had in fact been published the year before as An Accidence or the Path-way to Experience, subtitled:

Necessary for all young sea-men, or those that are desirous to goe to sea, briefly shewing the phrases, offices, and words of command, belonging to the building, ridging, and sayling, a man of warre; and how to manage a fight at sea. Together with the charge and duty of every officer, and their shares: also the names, weight, charge, shot, and powder, of all sorts of great ordnance. With the use of the petty tally.1

Given that Smith in his dictionary seems to deliberately obscure the phrase ‘chock-a-block’ by setting it instead as ‘block-a-block’, the episode of his captivity in the Ottoman lands stands out as particularly fascinating. Smith was a careful observer, even an early ethnologist, and in his memoir records in detail the customs of the peoples he encountered during his captivity: did he perhaps hear the phrase in Turkish, but then intentionally obscure it out of hatred for his enemy’s language? Yet it is risky, given the gulf of history, culture, and mentality that separates us from them, to speculate about the psychology of Elizabethan adventurers: if Smith did harbour resentment towards the Turks, this did not prevent him naming a region of the newly mapped area of New England after his ‘mistress’ in Istanbul.2 But in fact we can know for sure that the entry for ‘block-a-block’ in Sea Grammar is unconnected to Smith’s encounter with the Turks, for Sea Grammar is just An Accidence expanded by copying over the alphabetical entries from Henry Mainwaring’s Sea-Man’s Dictionary, and it is from Mainwaring’s book that Smith took the entry for ‘Block and block’ that is now recorded in the OED.

When we have upon any Tackle, Halliards, or the like, to which two Blocks do belong, when they meet and touch, we can hail no more, and this we call Block and Block. [Mainwaring, Sea-Man’s Dictionary, p. 8]3

By recounting Smith’s life we glimpse the resentment and conflict, but also the curiosity and communication, that marked relations between Europe and the Ottoman Empire in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Perhaps that resentment— ethnic, religious, imperial—is one of the social forces that functioned to keep the Turkish origins of ‘chock-a-block’ buried; and still functions, for that force is not extinct in the present day. But what about the Seaman’s Dictionary, from which Smith copied, and its author Henry Mainwaring?

The Bad Kind of Pirate

Sir Henry Mainwaring (1587‒1653) composed Seaman’s Dictionary between 1619 and 1623, while Lieutenant of Dover Castle. As a young man he proved himself as a sailor and soon became notorious among the Spanish for his piracy. He was later knighted and appointed to the Royal Navy, and briefly a member of parliament. On giving up piracy, he presented James I with his Discourse of Pirates, which gives details of their tactics and motivations, and concludes that, to suppress them, the king should never issue pirates with pardons:

To take away their hopes and encouragements, your Highness must put on a constant immutable resolution never to grant any pardon, and for those that are or may be taken, to put them all to death, or make slaves of them, for if your Highness should ask me when those men would leave offending I might answer, as a wise favourite did the late Queen, demanding when he would leave begging, he answered, when she would leave giving; so say I, when your Highness leaves pardoning.4

Remarkably, given that he offers this advice, he had himself been pardoned by James in 1616. As a nobleman—his family were landowners, and had been favoured by Queen Elizabeth—Mainwaring’s mode of piracy was more aligned towards the interests of the emerging British Empire than that of the outcasts and renegades who operated multi-ethnic and egalitarian ships and lived by the motto ‘A merry Life and a short one’.5 It was that kind of pirate Mainwaring despised.

Mainwaring was well aware of the dreadful conditions for seamen in the British Navy—poor wages, constant sickness, starvation rations, brutal punishment—and understood that they would be attracted to piracy: the threat of jail would not help to discipline the sailors ‘since their whole life for the most part is spent but in a running prison’; and he commends himself on having established conditions of ‘good civility and order’ in his own ships by ‘constant severity’ and by never forgiving any offence: ‘for questionless, as fear of punishment makes men doubtful to offend, so the hope of being pardoned makes them the apter to err’. He indeed understood so well that sailors would want to escape to the freedom and better conditions of pirate ships,6 that he considered it essential to limit the contact between officers of the British Navy and the crews of pirate ships:

further there must be a strict course, and duly executed, that no Vice-Admiral, or other, be suffered to speak with any of the pirates, but to forfeit either life or goods, for so long as they have any communication with them, so long will there be indirect dealing and relieving of them.7

In the English Civil War, Mainwaring sided with the Royalists, and died impoverished, with only ‘a horse and wearing apparel to the value of £8’.

Mainwaring’s story suggests a second force that might have been at work to obscure the origins of ‘chock-a-block’, this time the fear and resentment felt by the English nobility towards the common sailors, on whose skills they depended to make the expanding naval empire function. Mainwaring’s intention in composing Seaman’s Dictionary would later be eulogised as ‘rescuing from oblivion the language of the sea, and preserving it for the benefit of future generations’.8 But why would the language of the sea need rescuing from oblivion when British naval dominance was only just emerging? Perhaps by ‘oblivion’ is meant not that the language was threatened by disappearance in some future time, but that it then existed in the ‘oblivion’ represented by the minds and dialects of the common sailors, and needed to be reclaimed by the officer class who considered themselves the rightful masters of the sea. The efforts by Mainwaring to record the naval lexicon were intended to break the monopoly the sailors had on the technical vocabulary of the sea, and reassert the dominance of the nobility in this sphere.9

In this appropriation of the naval language by the upper classes, the natural tendency to invent etymologies to hide a gap in one’s knowledge is combined with contempt for the sailors’ own knowledge of the words they employed. In another entry Mainwaring gaily corrects the sailors in the use of ‘futtock’, a structural rib in a ship’s frame, claiming preposterously that this is a mispronunciation of the correct term which is ‘foot-hook’.10

Something similar, we may imagine, happened with çok kalabalık: among the sailors the word was already in use in its core meaning of ‘very crowded’, and Mainwaring either seized on a derivative use of the phrase for ropes and pulleys, or invented that new usage himself. In either case, having attached it to ropes and pulleys, he (and not originally Smith) now sees the need to explain to the commoners that the correct phrase is not ‘chock-a-block’, which he rightly thinks makes no sense as there is no ‘chock’ involved (Seaman’s Dictionary has a perfectly sensible entry for Choak), but rather ‘block-a-block’, reflecting the two blocks pressed together. Perhaps in Seaman’s Dictionary we are witnessing the very act of burying the origins of the Turkish expression; or perhaps the burial had already happened, and Mainwaring only cements it.

Paving over the burial site

But what, finally, of the etymologists and lexicographers whose job it is to trace and record words’ true origins? Why, in all these centuries, has this tiny yet delightful fact not been noticed? But it is only in comparatively recent history that the Turkish language has been a topic in the English centres of learning. When the British Army needed officers to staff the Allies’ occupation of Istanbul after World War I, it had to find new recruits and train them at the School of Oriental Studies,11 which had opened only in 1917. The compilers of dictionaries in Oxford and Cambridge could call on a long tradition of the study of Arabic and Hebrew, but not of Turkish.

English speakers who have sojourned in Turkey over the centuries might have been expected to spot the similarity, but it may have been that the few elites who were resident in the Ottoman lands long enough to learn the language would not have known the uncouth English vernacular ‘chock-a-block’ (and perhaps çok kalabalık too was considered uncouth in elite Ottoman circles). And while English and Turkish sailors certainly came into contact over the centuries (as the next post will explore), they may have communicated primarily in the Lingua franca, the commercial language of the Mediterranean; and in any case, those sailors who did know the true origin of the word—there must have been many—would not have had means or motivation to communicate this to Oxford and Cambridge.

While the naval officers resented the sailors and sought to appropriate their language, the landlubber authorities similarly deprecated the expertise of the naval classes and generally assumed that knowledge was only legitimate if it had been generated in their own universities. The cure for scurvy and the cause of malaria were known by seamen centuries before the metropolitan centres of medicine announced they had discovered them.12 What with prejudice against Turks, incuriosity by the officer class about the language of their subordinates, and a general prejudice by the British academics against anything they did not already know, the origins of ‘chock-a-block’ had little chance of being preserved.

These speculations point to how the etymology of ‘chock-a-block’ was buried, and has remained buried for so long, but do not suggest how the phrase was transferred to English in the first place. That’s a future topic.

Notes

- The text of An Accidence is available in various forms. See, for example, the University of Michigan website [link]. ↩︎

- Cape Tragabigzanda was renamed Cape Anne in 1614. See, for example, Mary Ellen Lepionka, ‘What’s in a Name: Tragabigzanda’, YouTube, 16 January 2019, [link]. ↩︎

- The Sea-Man’s Dictionary: or An Exposition and Demonstration of all the Parts and Things belonging to a Ship. Together with an Explanatios of all the Terms and Phrases used in the Practick of Navigation. Composed by that Able and Experienced Sea-Man Sir Henry Manwayring Knight. A 1644 edition is available on the internet archive [link]. ↩︎

- Henry Mainwaring, A Discourse on Pirates, ed. G. E. Mainwaring and W. E. Perrin (Naval Records Society, 1922) [link]. ↩︎

- ‘The attractions [of piracy] were perhaps best summarized by Bartholomew Roberts, who remarked that in the merchant service “there is thin Commons, low Wages, and hard Labour; in this, Plenty and Satiety, Pleasure and ease, Liberty and Power; and who would not ballance Creditor on this Side, when all the Hazard that is run for it, at worst, is only a sower look or two at choaking. No, a merry Life and a short one, shall be my motto.”’ Peter Lineburgh and Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra: The Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic (Verso, 2000), p. 168. ↩︎

- ‘The early-eighteenth-century pirate ship was a “world turned upside down,” made so by he articles of agreement that established the rules and customs of the pirates’ social order …’, ‘The pirate ship was democratic in an undemocratic age … ’. Lineburgh and Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra, p. 162. ↩︎

- Mainwaring, A Discourse on Pirates. ↩︎

- The Life and Works of Sir Henry Mainwaring, vol. 1, ed. G. E. Manwaring (London: Navy Records Society, 1922), p. xii. ↩︎

- The development of training programmes for sailors would also have been a means to this end. ‘The need for a book on seamanship and nautical terminology was recognized during the early 1600’s to adequately train future seaman and avoid losing England’s nautical pre-eminence of Queen Elizabeth’s reign’. P. L. Barbour, ‘Captain John Smith’s Sea Grammar and its Debt to Sir Henry Mainwaring’s “Seaman’s Dictionary”,’ The Mariner’s Mirror (1972) [link]. ↩︎

- ‘Futtocks. This word is commonly pronounced, but I think more properly it should be called Foot-hooks; for the Futtocks are those compassing timbers, which give the bredth and bearing to the ship, which are scarfed to the ground timbers: And because no timbers that compass can be found long enough, to go up through all the side of the ship, these compassing timbers are scarfed one into the other, and those next the Keel, are called the lower ground Futtocks, the other are called the upper Futtocks.’ (Seamans’ Dictionary p. 43)

So how ‘foot-hook’ could be the true name for a structural timber in a ship’s frame is not explained. Wiktionary speculates that it is Norse: ‘Perhaps came into Old English from Old Norse fótr, or fett / futt (big); + ek (timbr), or øks; giving Old Norse fót’ek, futtek or futtøks’ [link]. The English names for other important parts of ships are originally Norse, so this idea is attractive; but if it were a Norse word then the Scandinavian languages could be expected to have a similar word, but it seems they don’t: Swedish, zillror; Danish, ziters; Dutch, zillters; German, sitzer. John Fincham, An Outline of the Practice of Ship-Building (England: Portsea, 1825) [link]. ↩︎ - My grandfather was one of these students, which contributed to this topic becoming so interesting for me. J. G. Bennett, Witness (Santa Fe, NM: Bennett Books, 1997; orig. pub. Hodder & Stoughton, 1969), p. 5.

The creation of the School of Oriental Studies was hampered by the inveterate contempt of the British academic classes: ‘It is not only against indifference that the advocates of the School have had to struggle, but against a jealousy based on the conviction that the number of students of Oriental languages in the country was bound always to be strictly limited, and that the new School could only exist at the expense of its rivals. […] Our history is desperately longer than it ought to have been. It has taken ninety-nine years to set on foot a School of Oriental Studies on a scale at all adequate to the Metropolis of the British Empire, and even now the School has not the income regarded as a minimum by two Government Committees and a Royal Commission.’ P. J. Hartog, ‘The Origins of the School of Oriental Studies’, Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London 1, no. 1 (1917), p. 22. ↩︎ - C. Lloyd, British Seaman, 1200‒1860: A Social Survey (Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1970). ‘In 1572 a merchant captain drew attention to the association between mosquito bites and malaria, but no doctor took any notice until the end of the nineteenth century’ (p. 43). The cause of scurvy is regarded as having have been solved by surgeon James Lind in the 18th century, but in 1593 one Captain Richard Hawkins wrote that ‘sour oranges and lemons’ keep the disease at bay (p. 46). ↩︎

Leave a comment